Photo: Bryan Cox/ICE/AP

As hundreds of undocumented immigrants were rounded up across the country last February in the first mass raids of the Trump administration, Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials went out of their way to portray the people they detained as hardened criminals, instructing field offices to highlight the worst cases for the media and attempting to distract attention from the dozens of individuals who were apprehended despite having no criminal background at all.

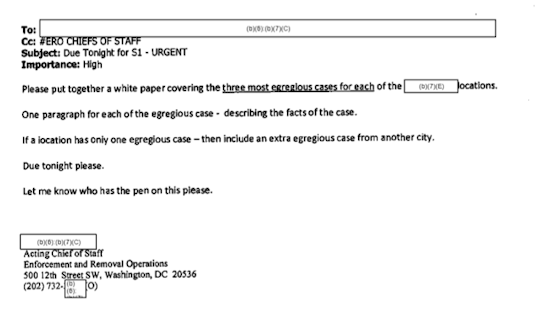

On February 10, as the raids kicked off, an ICE executive in Washington sent an “URGENT” directive to the agency’s chiefs of staff around the country. “Please put together a white paper covering the three most egregious cases,” for each location, the acting chief of staff of ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations wrote in the email. “If a location has only one egregious case — then include an extra egregious case from another city.”

The email indicated the assignment was due that night, but a day later, an agent at ICE’s San Antonio office sent an internal email saying the team had come up short. “I have been pinged by HQ this morning indicating that we failed at this tasking,” the agent wrote.

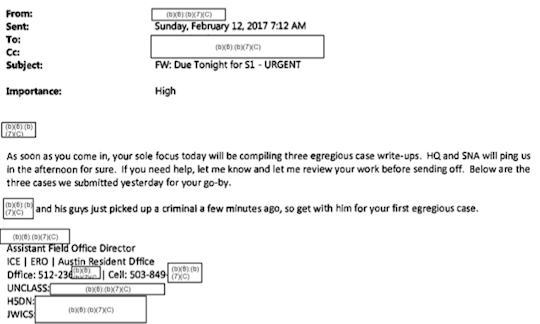

As the hours passed, the pressure on local agents to come up with something grew more intense. “As soon as you come in, your sole focus today will be compiling three egregious case write-ups,” an assistant field office director at the agency’s Austin Resident Office wrote to that team on February 12, noting that the national and San Antonio offices were growing impatient. “HQ and SNA will ping us in the afternoon for sure.”

Then the agent added that a team of officers had “just picked up a criminal a few minutes ago, so get with him for your first egregious case.”

A heavily redacted cache of emails, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by students at Vanderbilt University Law School and published exclusively by The Intercept, reveals how in the early days of Donald Trump’s presidency, ICE agents in Austin scrambled — and largely failed — to engineer a narrative that would substantiate the administration’s claims that the raids were motivated by public safety concerns. Instead, the emails detail the evolution of ICE’s public statements once it became obvious that the Trump administration’s narrative was not true.

Bob Libal, executive director of Grassroots Leadership, an Austin-based civil rights group, said the emails show just “how aggressive and desperate and duplicitous ICE was during these raids.”

“Essentially this is ICE trying to gin up a case for its actions, when really this isn’t at all about public safety,” he told The Intercept after reviewing the correspondence. “We can thoroughly expect that’s what they’re going to try to do again.”

ICE declined to comment for this article.

Starting on February 6, ICE conducted a nationwide sweep of undocumented immigrants in large and small cities across the country, quickly disseminating panic in immigrant communities. The raids — which led to 680 arrests nationwide — were the first in an ongoing series of mass enforcement operations ordered by the Trump administration. Last week, more than 450 people were arrested in a similar sweep the agency dubbed “Operation Safe City.”

At first, immigration officials said they were targeting public safety threats, such as individuals with criminal convictions and gang members. But while they sought to depict those swept up in the raids as dangerous criminals, it immediately became clear that many had only minor violations on their record, and that dozens had no criminal record at all. In Austin, where 51 people were arrested during the February raids, more than half had no criminal convictions. Many of those who did have criminal records were found guilty of drunken driving.

Within hours, stories of ICE’s aggressive tactics dominated the media, as Austin residents reported that agents had set up checkpoints on the street, detained a teenager, and mistakenly apprehended a legal resident with no criminal history as he dropped his kids off at school. As anxiety over the raids escalated, elected officials issued public condemnations, and local and national reporters inundated the agency’s Texas offices with requests for comment.

In their first media responses, ICE officials maintained the line that the raids were in the public interest, telling reporters that “by removing from the streets criminal aliens and other threats to the public, ICE helps improve public safety.”

As criticism escalated, ICE shifted to downplaying the operation as “no different than the routine,” telling reporters that the raids were the same “targeted arrests carried out by ICE’s Fugitive Operations Teams on a daily basis,” and suggesting off the record that claims to the opposite were “false, dangerous, and irresponsible.” As it became clear that dozens of individuals with no criminal history had been apprehended, ICE shifted gears and told reporters that in addition to targeting safety threats, the raids were always meant to target those whose only crimes were immigration-related, like re-entering the U.S. after deportation: “The president has been clear in saying that DHS should be focused on removing individuals who pose a threat to public safety, who have been charged with criminal offenses, who have committed multiple immigration violations or who have been deported and re-entered the country illegally.”

As they released their own statements, ICE officials were also monitoring elected officials’ public communications — and strategizing about how to respond to them.

“Congressman Castro is tweeting about ICEs enforcement operations taking place this weekend in south Texas,” an internal ICE email sent on February 10 read, forwarding a reporter’s query about Congressman Joaquin Castro’s statement of concern over the raids. “I’m responding to this reporter using our statement. But I’m not responding to what the Congressman is tweeting.” (Castro did not respond to a request for comment.)

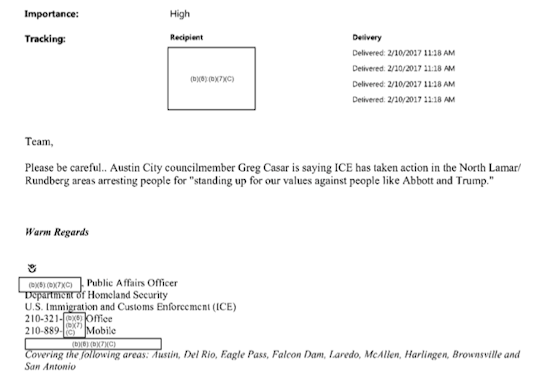

“Team, Please be careful.. Austin City councilmember Greg Casar is saying ICE has taken action in the North Lamar/ Rundberg areas arresting people for ‘standing up for our values against people like Abbott and Trump,’” a public information officer emailed in reference to a Facebook post by the council member.

“I think what those emails make very clear is that we have a federal law enforcement agency that’s willing to lie, just like Trump is willing to lie, in order to continue the criminalization of immigrant communities,” Casar told The Intercept after reviewing the emails. “We live in a really scary time where a federal law enforcement agency like ICE is essentially operating as a propaganda machine for the Trump administration.”

“They specifically went out of their way to mislead the public by searching for egregious cases,” he added. “And then you can see in the emails that they couldn’t find egregious cases.”

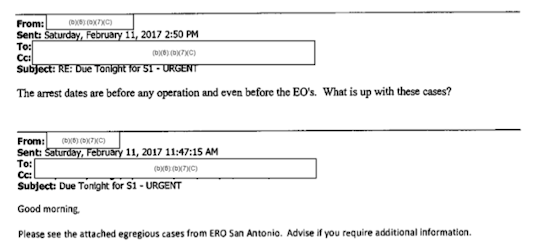

In fact, ICE’s attempts to provide “egregious” examples of criminals being apprehended in the raids were lagging, the emails suggest. On February 11, an official responded to a colleague’s list of egregious cases by pointing out that they were unrelated to the ongoing operation. “The arrest dates are before any operation and even before the EO’s. What is up with these cases?” the official wrote.

Eventually, ICE managed to promote the detention of a Salvadoran man who had pleaded guilty to sexual assault of a child, but the agency failed to provide more egregious examples — and the media focused instead on ICE’s own egregious tactics.

But many in the city felt that Austin was being targeted for a different reason — a political one.

Days after Trump’s election, Austin’s Sheriff-Elect Sally Hernandez, a Democrat, reiterated her campaign promise to turn Austin into Texas’s first “sanctuary city.” “The sheriff’s office will not be part of a deportation force that sacrifices hundreds and thousands of people, our neighbors, to a broken federal immigration system,” Hernandez said in November.

Hernandez, who was dubbed “sanctuary Sally” by conservative media, faced an uphill battle. Texas’s Republican Gov. Greg Abbott called her refusal to honor ICE requests a “betrayal” of her oath and cut $1.5 million in criminal justice-related grants to Travis County. In May, Abbott signed into law Senate Bill 4, or “SB4,” one of the harshest anti-sanctuary legislations in the country, the constitutionality of which is being disputed in court.

But as the battle over sanctuary cities is fought at the state level, the federal government has other ways to go after defiant local officials: It can make their cities targets for enforcement.

In Austin’s case, rumors that the raids there had been in retaliation for Hernandez’s stance against ICE swirled for weeks, and in March, they appeared to be confirmed by a federal judge who said in court that Austin was being targeted “as a result of the sheriff’s new policy.”

Andrew Austin, a U.S. magistrate judge in the city, made the remarks during a hearing in the case of Juan Coronilla-Guerrero, an undocumented Mexican immigrant who had been detained during the February raids. Coronilla-Guerrero’s case had alarmed immigrant advocates, lawyers, and — the hearing transcript shows — the judge himself because ICE had apprehended him as he exited a courthouse, where he had gone to clear two unrelated charges.

The hearing transcript reveals a level of confusion as court officials began to face the new administration’s immigration policies.

“So this isn’t totally germane, but you’re here and it gives me an opportunity to ask some questions because we’ve been wondering exactly what the new policies will be because things have changed a bit,” the judge said, addressing ICE agent Laron Bryant, one of the agents who arrested Coronilla-Guerrero, before proceeding to quiz him on what courts might expect to see from the new administration.

In that exchange, Austin also revealed that shortly before the raids had begun, he and a fellow judge had been briefed by a senior ICE agent about the upcoming operation, which came in response to Hernandez’s policy, “because the meetings that occurred between the field office director and the sheriff didn’t go very well,” he said.

In an email to The Intercept, Austin declined to comment “any further than what was said in court.” Mark Lane, the other federal judge, who, according to Austin, was also briefed by ICE, declined to comment. A spokesperson for Hernandez wrote in an email to The Intercept that the sheriff “won’t comment on an allegation based on supposition.”

ICE denied targeting Travis County, calling statements that the raids were retaliatory “rumors” and “inaccurate.” But by that point, few seemed to believe the agency. “I’m sorry that ICE lied to me because they told me there was not a target,” said Gerald Daugherty, Travis County’s Republican commissioner. “I have to think a judge is telling the truth.”

As accusations that the Austin raids were political payback piled up, the agency issued a statement saying that “more ICE operational activity is required to conduct at-large arrests in any law enforcement jurisdiction that fails to honor ICE immigration detainers.”

That was ostensibly the reasoning behind the raids in September as well, which the agency said “focused on cities and regions where ICE deportation officers are denied access to jails and prisons to interview suspected immigration violators or jurisdictions where ICE detainers are not honored.”

Immigration advocates say that the focus on sanctuary cities is “politically motivated.”

“Yet again, the Trump administration is attempting to terrorize immigrant communities, keep families in fear, and undermine the trust immigrants have in cities that refuse to subsidize federal immigration enforcement,” said Ana María Archila, co-executive director of the Center for Popular Democracy. “Knowing how often ICE has lied about the true purpose of their raids before, it is hard for us to believe any of their claims about Operation Safe City.”

ICE’s Acting Director Thomas Homan said in a statement announcing the more recent raids that ICE was being “forced to dedicate more resources to conduct at-large arrests in these communities.” But he was more blunt about the administration’s intention in a July interview, in which he called sanctuary cities “ludicrous” and made no secret of why he was going after them. “The president recognizes that you’ve got to have a true interior enforcement strategy to make it uncomfortable for them.”

That retaliation has already had an inhibiting effect on some local officials, said Casar, the Austin city council member. “They’re not saying they’re deploying extra federal agents to a dangerous area. … It’s retaliation based on a political reason, not based on any kind of law enforcement purpose,” he said. “These raids really are a terrifying tool and the idea that the Trump administration would specifically use those in places where there’s political disagreement is a really scary thing.”

When he and other local officials take action on immigration issues — for instance, by suing the state over SB4 — they now always ask themselves, “What is the level of potential exposure this has on our constituents?” Casar added. “That’s real political repression, and while it may sound great to say, ‘We just need to do it anyway because we can’t be intimidated by that’ — when you’re in the position of making those decisions, when there are real lives at stake, you really do have to think about it.”

There is no question that there are lives at stake.

While Austin’s comments on the retaliatory nature of the Travis County raids drew fleeting attention to the politicization of federal enforcement operations, Coronilla-Guerrero, the man whose case was under review that day, was eventually deported, despite his wife telling the judge that his life would be at risk in Mexico, from where he had fled because of gang threats.

Last month, armed men dragged Coronilla-Guerrero out of the relatives’ home where he had been staying in the state of Guanajuato, while he was asleep with one of his children. His body was found on the street the next morning.

Documents published with this article:

Update: Oct. 5, 2017

A spokesperson for ICE did not respond to questions by The Intercept but after publication of this article issued the following statement. “ICE clearly and directly communicates priority groups for various operations. Any suggestions that the agency intentionally misled individuals about target populations are completely false. While ICE does provide examples of significant arrests to proactively meet requests for this information, those examples are accompanied by a list of target groups. In the case of the February operation, the targeted groups of criminal aliens, illegal re-entrants, and immigration fugitives were listed in the headlines of each local announcement. A similar statement was included in the announcement of Operation Safe City. Furthermore, when outlining results, a clear number or percentage of criminal aliens arrested is included in the announcement.”

On February 10, as the raids kicked off, an ICE executive in Washington sent an “URGENT” directive to the agency’s chiefs of staff around the country. “Please put together a white paper covering the three most egregious cases,” for each location, the acting chief of staff of ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations wrote in the email. “If a location has only one egregious case — then include an extra egregious case from another city.”

The email indicated the assignment was due that night, but a day later, an agent at ICE’s San Antonio office sent an internal email saying the team had come up short. “I have been pinged by HQ this morning indicating that we failed at this tasking,” the agent wrote.

As the hours passed, the pressure on local agents to come up with something grew more intense. “As soon as you come in, your sole focus today will be compiling three egregious case write-ups,” an assistant field office director at the agency’s Austin Resident Office wrote to that team on February 12, noting that the national and San Antonio offices were growing impatient. “HQ and SNA will ping us in the afternoon for sure.”

Then the agent added that a team of officers had “just picked up a criminal a few minutes ago, so get with him for your first egregious case.”

A heavily redacted cache of emails, obtained through a Freedom of Information Act request by students at Vanderbilt University Law School and published exclusively by The Intercept, reveals how in the early days of Donald Trump’s presidency, ICE agents in Austin scrambled — and largely failed — to engineer a narrative that would substantiate the administration’s claims that the raids were motivated by public safety concerns. Instead, the emails detail the evolution of ICE’s public statements once it became obvious that the Trump administration’s narrative was not true.

Bob Libal, executive director of Grassroots Leadership, an Austin-based civil rights group, said the emails show just “how aggressive and desperate and duplicitous ICE was during these raids.”

“Essentially this is ICE trying to gin up a case for its actions, when really this isn’t at all about public safety,” he told The Intercept after reviewing the correspondence. “We can thoroughly expect that’s what they’re going to try to do again.”

ICE declined to comment for this article.

Starting on February 6, ICE conducted a nationwide sweep of undocumented immigrants in large and small cities across the country, quickly disseminating panic in immigrant communities. The raids — which led to 680 arrests nationwide — were the first in an ongoing series of mass enforcement operations ordered by the Trump administration. Last week, more than 450 people were arrested in a similar sweep the agency dubbed “Operation Safe City.”

At first, immigration officials said they were targeting public safety threats, such as individuals with criminal convictions and gang members. But while they sought to depict those swept up in the raids as dangerous criminals, it immediately became clear that many had only minor violations on their record, and that dozens had no criminal record at all. In Austin, where 51 people were arrested during the February raids, more than half had no criminal convictions. Many of those who did have criminal records were found guilty of drunken driving.

Within hours, stories of ICE’s aggressive tactics dominated the media, as Austin residents reported that agents had set up checkpoints on the street, detained a teenager, and mistakenly apprehended a legal resident with no criminal history as he dropped his kids off at school. As anxiety over the raids escalated, elected officials issued public condemnations, and local and national reporters inundated the agency’s Texas offices with requests for comment.

In their first media responses, ICE officials maintained the line that the raids were in the public interest, telling reporters that “by removing from the streets criminal aliens and other threats to the public, ICE helps improve public safety.”

As criticism escalated, ICE shifted to downplaying the operation as “no different than the routine,” telling reporters that the raids were the same “targeted arrests carried out by ICE’s Fugitive Operations Teams on a daily basis,” and suggesting off the record that claims to the opposite were “false, dangerous, and irresponsible.” As it became clear that dozens of individuals with no criminal history had been apprehended, ICE shifted gears and told reporters that in addition to targeting safety threats, the raids were always meant to target those whose only crimes were immigration-related, like re-entering the U.S. after deportation: “The president has been clear in saying that DHS should be focused on removing individuals who pose a threat to public safety, who have been charged with criminal offenses, who have committed multiple immigration violations or who have been deported and re-entered the country illegally.”

As they released their own statements, ICE officials were also monitoring elected officials’ public communications — and strategizing about how to respond to them.

“Congressman Castro is tweeting about ICEs enforcement operations taking place this weekend in south Texas,” an internal ICE email sent on February 10 read, forwarding a reporter’s query about Congressman Joaquin Castro’s statement of concern over the raids. “I’m responding to this reporter using our statement. But I’m not responding to what the Congressman is tweeting.” (Castro did not respond to a request for comment.)

“Team, Please be careful.. Austin City councilmember Greg Casar is saying ICE has taken action in the North Lamar/ Rundberg areas arresting people for ‘standing up for our values against people like Abbott and Trump,’” a public information officer emailed in reference to a Facebook post by the council member.

“I think what those emails make very clear is that we have a federal law enforcement agency that’s willing to lie, just like Trump is willing to lie, in order to continue the criminalization of immigrant communities,” Casar told The Intercept after reviewing the emails. “We live in a really scary time where a federal law enforcement agency like ICE is essentially operating as a propaganda machine for the Trump administration.”

“They specifically went out of their way to mislead the public by searching for egregious cases,” he added. “And then you can see in the emails that they couldn’t find egregious cases.”

In fact, ICE’s attempts to provide “egregious” examples of criminals being apprehended in the raids were lagging, the emails suggest. On February 11, an official responded to a colleague’s list of egregious cases by pointing out that they were unrelated to the ongoing operation. “The arrest dates are before any operation and even before the EO’s. What is up with these cases?” the official wrote.

Eventually, ICE managed to promote the detention of a Salvadoran man who had pleaded guilty to sexual assault of a child, but the agency failed to provide more egregious examples — and the media focused instead on ICE’s own egregious tactics.

Retaliatory Raids

Of all cities targeted in the February raids, Austin yielded the highest percentage of non-criminal apprehensions — more than half, according to a review by the Austin American-Statesman showing that 28 of the 51 people detained had committed no crime other than entering the country illegally. ICE dismissed such arrests as “collateral apprehensions,” suggesting that those apprehended were picked up because they might have been with someone who was wanted.But many in the city felt that Austin was being targeted for a different reason — a political one.

Days after Trump’s election, Austin’s Sheriff-Elect Sally Hernandez, a Democrat, reiterated her campaign promise to turn Austin into Texas’s first “sanctuary city.” “The sheriff’s office will not be part of a deportation force that sacrifices hundreds and thousands of people, our neighbors, to a broken federal immigration system,” Hernandez said in November.

Hernandez, who was dubbed “sanctuary Sally” by conservative media, faced an uphill battle. Texas’s Republican Gov. Greg Abbott called her refusal to honor ICE requests a “betrayal” of her oath and cut $1.5 million in criminal justice-related grants to Travis County. In May, Abbott signed into law Senate Bill 4, or “SB4,” one of the harshest anti-sanctuary legislations in the country, the constitutionality of which is being disputed in court.

But as the battle over sanctuary cities is fought at the state level, the federal government has other ways to go after defiant local officials: It can make their cities targets for enforcement.

In Austin’s case, rumors that the raids there had been in retaliation for Hernandez’s stance against ICE swirled for weeks, and in March, they appeared to be confirmed by a federal judge who said in court that Austin was being targeted “as a result of the sheriff’s new policy.”

Andrew Austin, a U.S. magistrate judge in the city, made the remarks during a hearing in the case of Juan Coronilla-Guerrero, an undocumented Mexican immigrant who had been detained during the February raids. Coronilla-Guerrero’s case had alarmed immigrant advocates, lawyers, and — the hearing transcript shows — the judge himself because ICE had apprehended him as he exited a courthouse, where he had gone to clear two unrelated charges.

The hearing transcript reveals a level of confusion as court officials began to face the new administration’s immigration policies.

“So this isn’t totally germane, but you’re here and it gives me an opportunity to ask some questions because we’ve been wondering exactly what the new policies will be because things have changed a bit,” the judge said, addressing ICE agent Laron Bryant, one of the agents who arrested Coronilla-Guerrero, before proceeding to quiz him on what courts might expect to see from the new administration.

In that exchange, Austin also revealed that shortly before the raids had begun, he and a fellow judge had been briefed by a senior ICE agent about the upcoming operation, which came in response to Hernandez’s policy, “because the meetings that occurred between the field office director and the sheriff didn’t go very well,” he said.

In an email to The Intercept, Austin declined to comment “any further than what was said in court.” Mark Lane, the other federal judge, who, according to Austin, was also briefed by ICE, declined to comment. A spokesperson for Hernandez wrote in an email to The Intercept that the sheriff “won’t comment on an allegation based on supposition.”

ICE denied targeting Travis County, calling statements that the raids were retaliatory “rumors” and “inaccurate.” But by that point, few seemed to believe the agency. “I’m sorry that ICE lied to me because they told me there was not a target,” said Gerald Daugherty, Travis County’s Republican commissioner. “I have to think a judge is telling the truth.”

As accusations that the Austin raids were political payback piled up, the agency issued a statement saying that “more ICE operational activity is required to conduct at-large arrests in any law enforcement jurisdiction that fails to honor ICE immigration detainers.”

That was ostensibly the reasoning behind the raids in September as well, which the agency said “focused on cities and regions where ICE deportation officers are denied access to jails and prisons to interview suspected immigration violators or jurisdictions where ICE detainers are not honored.”

Immigration advocates say that the focus on sanctuary cities is “politically motivated.”

“Yet again, the Trump administration is attempting to terrorize immigrant communities, keep families in fear, and undermine the trust immigrants have in cities that refuse to subsidize federal immigration enforcement,” said Ana María Archila, co-executive director of the Center for Popular Democracy. “Knowing how often ICE has lied about the true purpose of their raids before, it is hard for us to believe any of their claims about Operation Safe City.”

ICE’s Acting Director Thomas Homan said in a statement announcing the more recent raids that ICE was being “forced to dedicate more resources to conduct at-large arrests in these communities.” But he was more blunt about the administration’s intention in a July interview, in which he called sanctuary cities “ludicrous” and made no secret of why he was going after them. “The president recognizes that you’ve got to have a true interior enforcement strategy to make it uncomfortable for them.”

That retaliation has already had an inhibiting effect on some local officials, said Casar, the Austin city council member. “They’re not saying they’re deploying extra federal agents to a dangerous area. … It’s retaliation based on a political reason, not based on any kind of law enforcement purpose,” he said. “These raids really are a terrifying tool and the idea that the Trump administration would specifically use those in places where there’s political disagreement is a really scary thing.”

When he and other local officials take action on immigration issues — for instance, by suing the state over SB4 — they now always ask themselves, “What is the level of potential exposure this has on our constituents?” Casar added. “That’s real political repression, and while it may sound great to say, ‘We just need to do it anyway because we can’t be intimidated by that’ — when you’re in the position of making those decisions, when there are real lives at stake, you really do have to think about it.”

There is no question that there are lives at stake.

While Austin’s comments on the retaliatory nature of the Travis County raids drew fleeting attention to the politicization of federal enforcement operations, Coronilla-Guerrero, the man whose case was under review that day, was eventually deported, despite his wife telling the judge that his life would be at risk in Mexico, from where he had fled because of gang threats.

Last month, armed men dragged Coronilla-Guerrero out of the relatives’ home where he had been staying in the state of Guanajuato, while he was asleep with one of his children. His body was found on the street the next morning.

Documents published with this article:

Update: Oct. 5, 2017

A spokesperson for ICE did not respond to questions by The Intercept but after publication of this article issued the following statement. “ICE clearly and directly communicates priority groups for various operations. Any suggestions that the agency intentionally misled individuals about target populations are completely false. While ICE does provide examples of significant arrests to proactively meet requests for this information, those examples are accompanied by a list of target groups. In the case of the February operation, the targeted groups of criminal aliens, illegal re-entrants, and immigration fugitives were listed in the headlines of each local announcement. A similar statement was included in the announcement of Operation Safe City. Furthermore, when outlining results, a clear number or percentage of criminal aliens arrested is included in the announcement.”

Top photo: In this photo provided by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, ICE agents at a home in Atlanta, during a targeted enforcement operation on Feb. 9, 2017.

We depend on the support of readers like you to help keep our nonprofit newsroom strong and independent. Join Us

No comments:

Post a Comment